In Order to Remember His Lines for the Play He Repeates Over and Over Again

Chapter 9. Remembering and Judging

nine.1 Memories as Types and Stages

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast explicit and implicit memory, identifying the features that define each.

- Explain the function and duration of eidetic and echoic memories.

- Summarize the capacities of curt-term retention and explain how working memory is used to process information in information technology.

As you can see in Table 9.1, "Retentiveness Conceptualized in Terms of Types, Stages, and Processes," psychologists conceptualize retention in terms of types, in terms of stages, and in terms of processes. In this section we volition consider the two types of retentivity, explicit memory and implicit memory, and and so the iii major retention stages: sensory, short-term, and long-term (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968). Then, in the next section, we will consider the nature of long-term memory, with a detail emphasis on the cognitive techniques we can use to amend our memories. Our discussion will focus on the three processes that are cardinal to long-term retention: encoding, storage, and retrieval.

| As types |

|

| As stages |

|

| As processes |

|

Explicit Retentivity

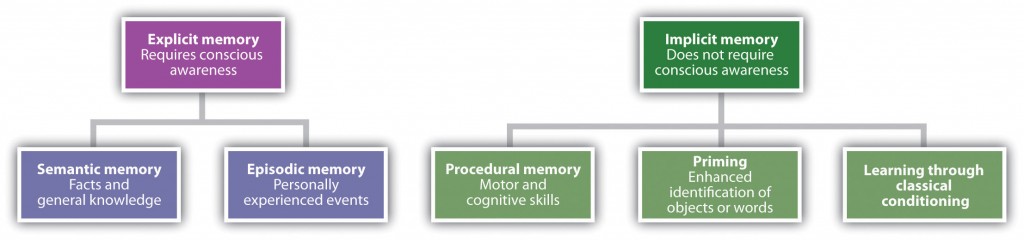

When we appraise memory by asking a person to consciously remember things, we are measuring explicit retention. Explicit retentiveness refers to cognition or experiences that can be consciously remembered. As y'all tin meet in Figure 9.2, "Types of Memory," there are two types of explicit retentiveness: episodic and semantic. Episodic memory refers to the firsthand experiences that we take had (e.g., recollections of our high school graduation twenty-four hours or of the fantastic dinner we had in New York last year). Semantic memory refers to our knowledge of facts and concepts almost the world (e.m., that the absolute value of −90 is greater than the absolute value of ix and that one definition of the discussion "affect" is "the experience of feeling or emotion").

Explicit memory is assessed using measures in which the individual being tested must consciously attempt to remember the data. A think memory examination is a mensurate of explicit memory that involves bringing from retention information that has previously been remembered. We rely on our recall retentiveness when we take an essay test, considering the test requires united states of america to generate previously remembered data. A multiple-pick test is an example of a recognition retention examination, a measure of explicit retentiveness that involves determining whether information has been seen or learned before.

Your own experiences taking tests will probably lead you to agree with the scientific enquiry finding that recall is more than difficult than recognition. Recall, such as required on essay tests, involves 2 steps: get-go generating an respond and so determining whether it seems to be the correct one. Recognition, as on multiple-choice test, simply involves determining which item from a listing seems nearly right (Haist, Shimamura, & Squire, 1992). Although they involve dissimilar processes, call back and recognition memory measures tend to be correlated. Students who practise better on a multiple-choice exam will likewise, mostly, do amend on an essay test (Bridgeman & Morgan, 1996).

A third way of measuring memory is known as relearning (Nelson, 1985). Measures of relearning (or savings) assess how much more than apace information is candy or learned when it is studied once more subsequently information technology has already been learned but then forgotten. If you take taken some French courses in the past, for instance, you might have forgotten well-nigh of the vocabulary you lot learned. Simply if you lot were to work on your French over again, you'd acquire the vocabulary much faster the second fourth dimension around. Relearning can exist a more sensitive measure of memory than either recall or recognition because it allows assessing retention in terms of "how much" or "how fast" rather than simply "correct" versus "incorrect" responses. Relearning also allows united states of america to mensurate memory for procedures like driving a car or playing a piano piece, as well as retention for facts and figures.

Implicit Memory

While explicit memory consists of the things that we tin consciously report that we know, implicit retentivity refers to noesis that we cannot consciously admission. However, implicit memory is nevertheless exceedingly of import to us because it has a direct consequence on our behaviour. Implicit memory refers to the influence of feel on behaviour, even if the individual is non aware of those influences. As you can see in Effigy 9.ii, "Types of Memory," in that location are iii general types of implicit retentivity: procedural memory, classical workout effects, and priming.

Procedural memory refers to our ofttimes unexplainable knowledge of how to do things. When nosotros walk from one place to another, speak to another person in English, dial a cell telephone, or play a video game, we are using procedural retention. Procedural retentiveness allows u.s.a. to perform complex tasks, even though we may not be able to explicate to others how nosotros do them. There is no manner to tell someone how to ride a wheel; a person has to larn by doing it. The idea of implicit retentiveness helps explain how infants are able to learn. The ability to clamber, walk, and talk are procedures, and these skills are easily and efficiently developed while we are children despite the fact that equally adults we have no conscious memory of having learned them.

A second type of implicit memory is classical workout furnishings, in which we larn, often without try or awareness, to associate neutral stimuli (such as a sound or a light) with some other stimulus (such as nutrient), which creates a naturally occurring response, such as enjoyment or salivation. The retentiveness for the association is demonstrated when the conditioned stimulus (the sound) begins to create the same response as the unconditioned stimulus (the food) did earlier the learning.

The terminal blazon of implicit memory is known equally priming, or changes in behaviour equally a result of experiences that accept happened frequently or recently. Priming refers both to the activation of knowledge (east.thou., we can prime number the concept of kindness by presenting people with words related to kindness) and to the influence of that activation on behaviour (people who are primed with the concept of kindness may human action more kindly).

Ane measure of the influence of priming on implicit retentiveness is the word fragment test, in which a person is asked to fill in missing letters to brand words. Y'all can try this yourself: First, endeavor to complete the following word fragments, but work on each i for only 3 or iv seconds. Do any words pop into mind quickly?

_ i b _ a _ y

_ h _ southward _ _ i _ n

_ o _ k

_ h _ i s _

Now read the following sentence carefully:

"He got his materials from the shelves, checked them out, and so left the building."

Then try again to make words out of the discussion fragments.

I retrieve you might discover that it is easier to complete fragments 1 and three as "library" and "book," respectively, after you read the sentence than it was before y'all read information technology. However, reading the sentence didn't really help you to consummate fragments ii and 4 equally "physician" and "chaise." This deviation in implicit retentivity probably occurred because equally you read the sentence, the concept of "library" (and perhaps "book") was primed, even though they were never mentioned explicitly. Once a concept is primed it influences our behaviours, for instance, on give-and-take fragment tests.

Our everyday behaviours are influenced by priming in a wide variety of situations. Seeing an advertisement for cigarettes may make us start smoking, seeing the flag of our home country may arouse our patriotism, and seeing a student from a rival school may arouse our competitive spirit. And these influences on our behaviours may occur without our being aware of them.

Enquiry Focus: Priming Outside Awareness Influences Behaviour

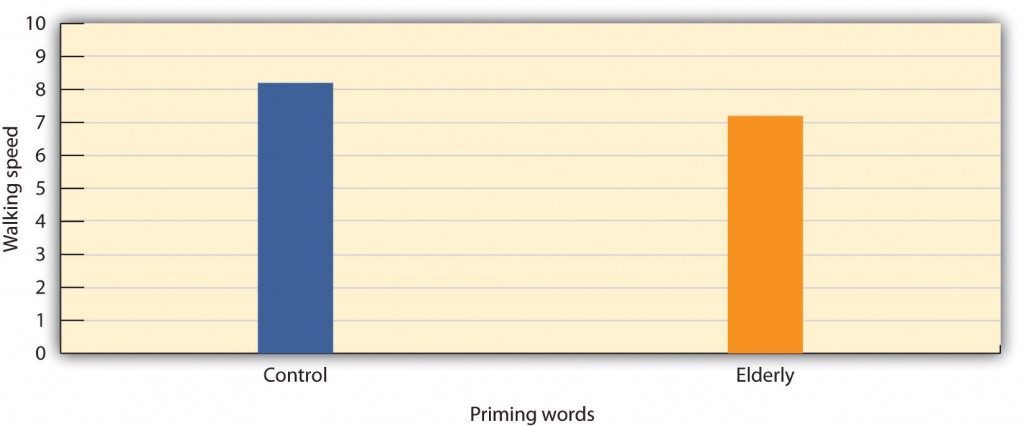

One of the nearly important characteristics of implicit memories is that they are oftentimes formed and used automatically, without much try or awareness on our part. In one demonstration of the automaticity and influence of priming effects, John Bargh and his colleagues (Bargh, Chen, & Burrows, 1996) conducted a written report in which they showed undergraduate students lists of five scrambled words, each of which they were to brand into a sentence. Furthermore, for one-half of the research participants, the words were related to stereotypes of the elderly. These participants saw words such as the following:

in Victoria retired live people

bingo man the forgetful plays

The other half of the research participants too made sentences, but from words that had nothing to exercise with elderly stereotypes. The purpose of this task was to prime stereotypes of elderly people in memory for some of the participants but not for others.

The experimenters then assessed whether the priming of elderly stereotypes would have any result on the students' behaviour — and indeed it did. When the research participant had gathered all of his or her belongings, thinking that the experiment was over, the experimenter thanked him or her for participating and gave directions to the closest elevator. And so, without the participants knowing it, the experimenters recorded the amount of time that the participant spent walking from the doorway of the experimental room toward the elevator. As you can see in Figure 9.3, "Research Results." participants who had made sentences using words related to elderly stereotypes took on the behaviours of the elderly — they walked significantly more slowly as they left the experimental room.

To make up one's mind if these priming furnishings occurred out of the awareness of the participants, Bargh and his colleagues asked nevertheless another group of students to complete the priming task and then to betoken whether they thought the words they had used to brand the sentences had any relationship to each other, or could possibly have influenced their behaviour in whatever style. These students had no awareness of the possibility that the words might accept been related to the elderly or could take influenced their behaviour.

Stages of Memory: Sensory, Brusk-Term, and Long-Term Retentivity

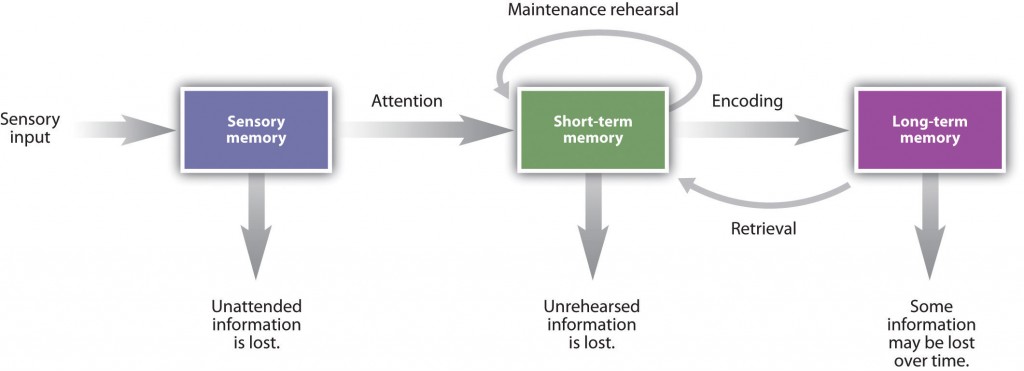

Another mode of agreement memory is to think nigh it in terms of stages that describe the length of fourth dimension that data remains available to us. According to this arroyo (run into Figure 9.4, "Memory Duration"), information begins in sensory memory, moves to short-term retention, and eventually moves to long-term memory. But not all data makes information technology through all 3 stages; most of information technology is forgotten. Whether the information moves from shorter-duration retention into longer-duration memory or whether it is lost from memory entirely depends on how the information is attended to and candy.

Sensory Memory

Sensory retention refers to the cursory storage of sensory data. Sensory memory is a memory buffer that lasts just very briefly and and then, unless it is attended to and passed on for more processing, is forgotten. The purpose of sensory retention is to give the brain some time to process the incoming sensations, and to let united states to run into the globe every bit an unbroken stream of events rather than as individual pieces.

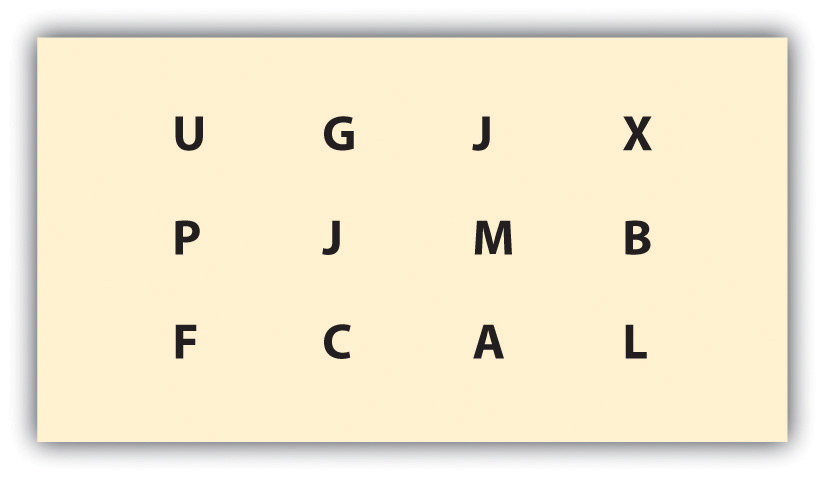

Visual sensory retentivity is known as iconic memory. Iconic memory was first studied by the psychologist George Sperling (1960). In his research, Sperling showed participants a display of letters in rows, like to that shown in Figure 9.5, "Measuring Iconic Retentiveness." However, the display lasted only well-nigh 50 milliseconds (1/20 of a 2d). Then, Sperling gave his participants a recall exam in which they were asked to name all the letters that they could retrieve. On average, the participants could think only about i-quarter of the messages that they had seen.

Sperling reasoned that the participants had seen all the letters simply could call back them only very briefly, making it impossible for them to report them all. To test this idea, in his next experiment, he commencement showed the same letters, only and so after the display had been removed, he signaled to the participants to written report the letters from either the first, 2nd, or third row. In this condition, the participants now reported almost all the letters in that row. This finding confirmed Sperling's hunch: participants had access to all of the letters in their iconic memories, and if the task was short enough, they were able to written report on the function of the display he asked them to. The "short enough" is the length of iconic retention, which turns out to exist about 250 milliseconds (¼ of a second).

Auditory sensory retentiveness is known as echoic memory. In contrast to iconic memories, which decay very rapidly, echoic memories tin can last as long every bit four seconds (Cowan, Lichty, & Grove, 1990). This is convenient as information technology allows you — among other things — to remember the words that you said at the starting time of a long judgement when you get to the end of it, and to take notes on your psychology professor's most contempo argument even after he or she has finished proverb it.

In some people iconic retention seems to last longer, a phenomenon known equally eidetic imagery (or photographic memory) in which people tin written report details of an paradigm over long periods of time. These people, who oft suffer from psychological disorders such as autism, claim that they can "come across" an image long after it has been presented, and can frequently report accurately on that image. At that place is also some evidence for eidetic memories in hearing; some people report that their echoic memories persist for unusually long periods of fourth dimension. The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart may have possessed eidetic memory for music, because even when he was very young and had non yet had a great bargain of musical training, he could heed to long compositions and then play them dorsum virtually perfectly (Solomon, 1995).

Short-Term Memory

Virtually of the information that gets into sensory retentiveness is forgotten, but information that nosotros turn our attention to, with the goal of remembering information technology, may pass into short-term memory. Short-term memory (STM) is the place where pocket-size amounts of data can exist temporarily kept for more than than a few seconds but normally for less than one infinitesimal (Baddeley, Vallar, & Shallice, 1990). Data in short-term retentiveness is not stored permanently but rather becomes available for us to process, and the processes that nosotros use to make sense of, modify, interpret, and shop information in STM are known every bit working retentiveness.

Although it is called memory, working memory is non a store of memory like STM only rather a set of memory procedures or operations. Imagine, for instance, that you are asked to participate in a task such every bit this one, which is a measure of working memory (Unsworth & Engle, 2007). Each of the following questions appears individually on a computer screen and and then disappears after you lot answer the question:

| Is x × 2 − 5 = xv? (Reply YES OR NO) Then remember "S" | |

| Is 12 ÷ half-dozen − 2 = ane? (Answer YES OR NO) Then remember "R" | |

| Is ten × two = five? (Answer Yep OR NO) Then remember "P" | |

| Is viii ÷ 2 − 1 = 1? (Reply YES OR NO) Then remember "T" | |

| Is 6 × 2 − 1 = viii? (Reply Yeah OR NO) And so retrieve "U" | |

| Is 2 × 3 − 3 = 0? (Answer Yeah OR NO) Then recall "Q" |

To successfully accomplish the task, you take to answer each of the math issues correctly and at the aforementioned time remember the letter that follows the task. Then, after the vi questions, you must list the letters that appeared in each of the trials in the correct order (in this instance S, R, P, T, U, Q).

To attain this hard task you demand to use a diverseness of skills. You clearly demand to use STM, equally y'all must continue the messages in storage until you are asked to list them. Only you too need a way to make the best use of your available attending and processing. For example, you might decide to use a strategy of echo the letters twice, then quickly solve the next problem, and and so repeat the letters twice again including the new i. Keeping this strategy (or others like information technology) going is the role of working memory'southward cardinal executive—the office of working retentivity that directs attention and processing. The central executive will make use of whatsoever strategies seem to exist best for the given job. For instance, the central executive volition direct the rehearsal procedure, and at the aforementioned time straight the visual cortex to course an image of the list of letters in memory. You tin see that although STM is involved, the processes that nosotros use to operate on the cloth in retentivity are likewise disquisitional.

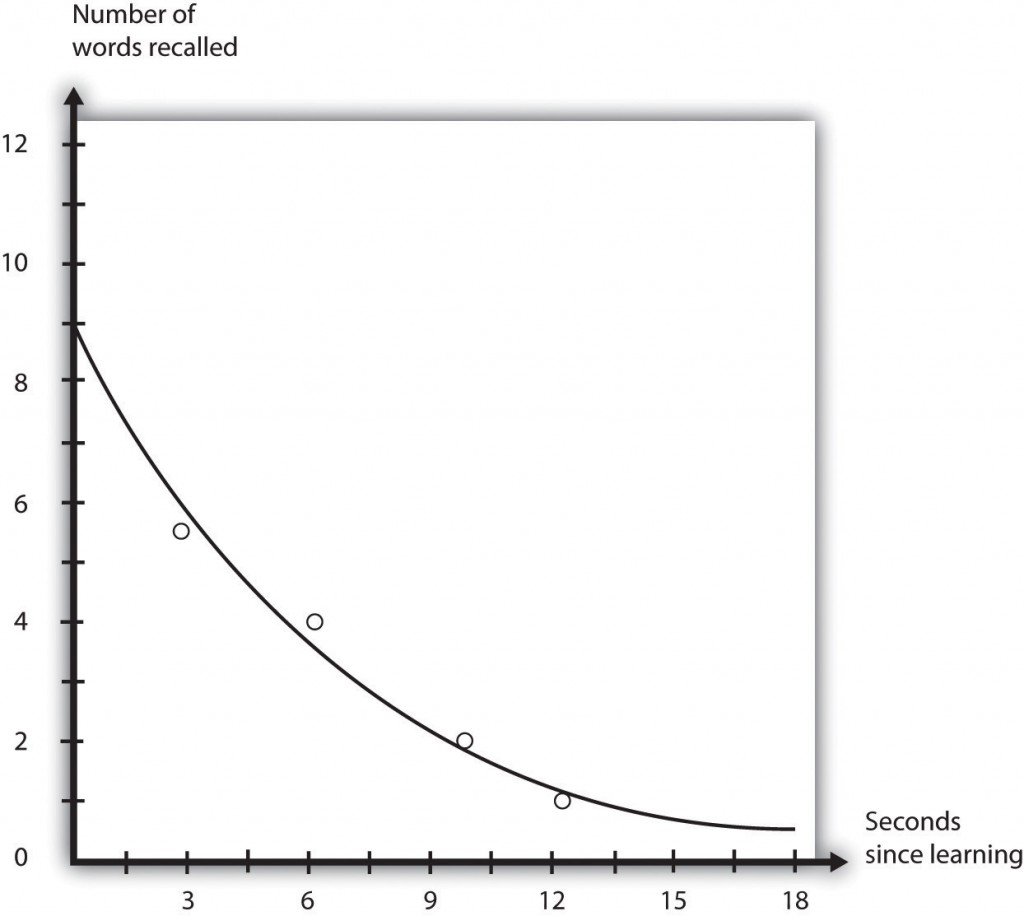

Brusk-term memory is express in both the length and the amount of data it can hold. Peterson and Peterson (1959) found that when people were asked to remember a list of three-letter strings and then were immediately asked to perform a distracting task (counting backward by threes), the material was quickly forgotten (come across Figure nine.six, "STM Decay"), such that by 18 seconds it was nigh gone.

1 manner to prevent the decay of information from short-term memory is to use working memory to rehearse it. Maintenance rehearsal is the process of repeating data mentally or out loud with the goal of keeping it in memory. Nosotros engage in maintenance rehearsal to keep something that we want to recollect (e.g., a person's name, email accost, or phone number) in mind long enough to write information technology downwards, utilise information technology, or potentially transfer it to long-term memory.

If we proceed to rehearse information, it will stay in STM until we stop rehearsing it, only in that location is also a capacity limit to STM. Try reading each of the following rows of numbers, one row at a time, at a charge per unit of about one number each second. Then when you have finished each row, shut your eyes and write down every bit many of the numbers as you can remember.

019

3586

10295

861059

1029384

75674834

657874104

6550423897

If you are like the average person, you will have institute that on this exam of working retention, known as a digit span test, you did pretty well up to about the fourth line, and so you started having problem. I bet you lot missed some of the numbers in the concluding three rows, and did pretty poorly on the last ane.

The digit span of most adults is betwixt five and nine digits, with an average of most seven. The cerebral psychologist George Miller (1956) referred to "seven plus or minus two" pieces of information as the magic number in curt-term memory. But if nosotros can only hold a maximum of about nine digits in short-term memory, and then how tin can nosotros remember larger amounts of information than this? For case, how can we ever call up a 10-digit phone number long enough to dial it?

One mode we are able to expand our ability to recollect things in STM is by using a retention technique called chunking. Chunking is the procedure of organizing data into smaller groupings (chunks), thereby increasing the number of items that tin can exist held in STM. For instance, try to call up this cord of 12 letters:

XOFCBANNCVTM

You probably won't do that well considering the number of messages is more than the magic number of 7.

Now attempt once again with this one:

CTVCBCTSNHBO

Would it help you if I pointed out that the material in this string could be chunked into four sets of three letters each? I think it would, because then rather than remembering 12 letters, you would only have to remember the names of four television stations. In this case, chunking changes the number of items you have to recall from 12 to only four.

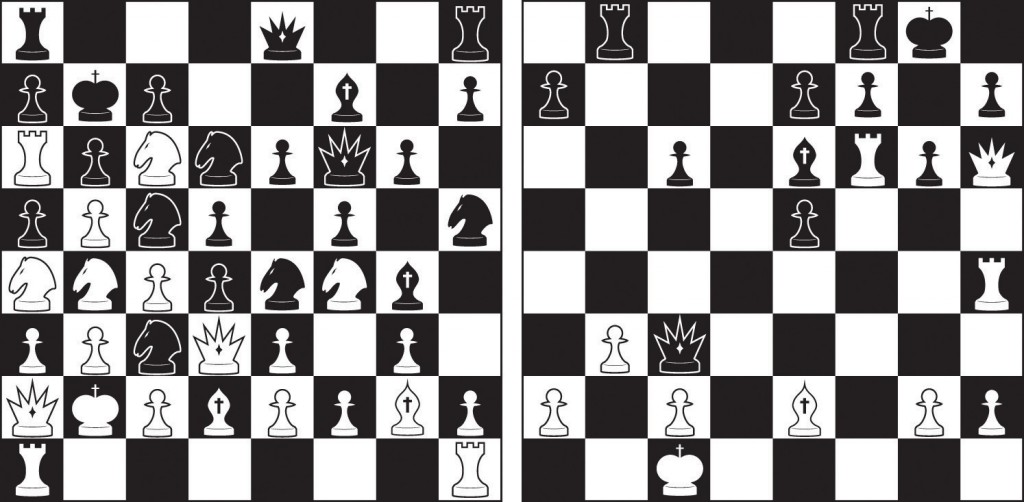

Experts rely on chunking to aid them process complex data. Herbert Simon and William Chase (1973) showed chess masters and chess novices diverse positions of pieces on a chessboard for a few seconds each. The experts did a lot ameliorate than the novices in remembering the positions because they were able to run into the "big motion-picture show." They didn't have to remember the position of each of the pieces individually, but chunked the pieces into several larger layouts. But when the researchers showed both groups random chess positions — positions that would be very unlikely to occur in real games — both groups did equally poorly, because in this situation the experts lost their power to organize the layouts (see Figure 9.7, "Possible and Incommunicable Chess Positions"). The same occurs for basketball. Basketball players recollect actual basketball positions much ameliorate than do nonplayers, but merely when the positions make sense in terms of what is happening on the court, or what is probable to happen in the most future, and thus tin can exist chunked into bigger units (Didierjean & Marmèche, 2005).

If data makes it by brusque term-retentiveness it may enter long-term retentiveness (LTM), memory storage that tin can concord information for days, months, and years. The chapters of long-term retentiveness is big, and at that place is no known limit to what nosotros can call back (Wang, Liu, & Wang, 2003). Although we may forget at to the lowest degree some information later on we larn it, other things will stay with united states forever. In the side by side section we will talk over the principles of long-term memory.

Key Takeaways

- Memory refers to the ability to store and retrieve information over time.

- For some things our memory is very good, but our active cognitive processing of data ensures that retentiveness is never an exact replica of what nosotros accept experienced.

- Explicit memory refers to experiences that tin exist intentionally and consciously remembered, and it is measured using think, recognition, and relearning. Explicit memory includes episodic and semantic memories.

- Measures of relearning (also known as "savings") assess how much more chop-chop information is learned when it is studied again afterwards it has already been learned only and so forgotten.

- Implicit retention refers to the influence of experience on behaviour, even if the individual is not aware of those influences. The three types of implicit memory are procedural memory, classical conditioning, and priming.

- Information processing begins in sensory memory, moves to short-term memory, and eventually moves to long-term retentiveness.

- Maintenance rehearsal and chunking are used to continue data in short-term memory.

- The capacity of long-term retentiveness is large, and there is no known limit to what we can recall.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Listing some situations in which sensory memory is useful for you lot. What exercise you think your experience of the stimuli would be like if you had no sensory memory?

- Depict a situation in which you need to use working retentivity to perform a task or solve a problem. How practise your working retentiveness skills help you?

References

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. Yard. (1968). Human retentiveness: A proposed system and its control processes. In K. Spence (Ed.),The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 2). Oxford, England: Academic Press.

Baddeley, A. D., Vallar, Thou., & Shallice, T. (1990). The development of the concept of working retention: Implications and contributions of neuropsychology. In Chiliad. Vallar & T. Shallice (Eds.),Neuropsychological impairments of short-term memory (pp. 54–73). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bargh, J. A., Chen, Chiliad., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social beliefs: Directly effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action.Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 71, 230–244.

Bridgeman, B., & Morgan, R. (1996). Success in higher for students with discrepancies between performance on multiple-choice and essay tests.Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(2), 333–340.

Cowan, N., Lichty, W., & Grove, T. R. (1990). Properties of memory for unattended spoken syllables.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, xvi(ii), 258–268.

Didierjean, A., & Marmèche, Due east. (2005). Anticipatory representation of visual basketball scenes by novice and expert players.Visual Noesis, 12(ii), 265–283.

Haist, F., Shimamura, A. P., & Squire, Fifty. R. (1992). On the relationship between recall and recognition retention.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 18(iv), 691–702.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number 7, plus or minus ii: Some limits on our capacity for processing information.Psychological Review, 63(ii), 81–97.

Nelson, T. O. (1985). Ebbinghaus's contribution to the measurement of retention: Savings during relearning.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11(3), 472–478.

Peterson, Fifty., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items.Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58(three), 193–198.

Simon, H. A., & Chase, Due west. Chiliad. (1973). Skill in chess.American Scientist, 61(4), 394–403.

Solomon, M. (1995).Mozart: A life. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Sperling, G. (1960). The information available in cursory visual presentation.Psychological Monographs, 74(eleven), i–29.

Unsworth, N., & Engle, R. West. (2007). On the division of brusque-term and working retention: An examination of elementary and circuitous span and their relation to higher order abilities.Psychological Bulletin, 133(6), 1038–1066.

Wang, Y., Liu, D., & Wang, Y. (2003). Discovering the chapters of human memory.Encephalon & Mind, four(2), 189–198.

Image Attributions

Figure 9.4: Adjusted from Atkinson & Shiffrin (1968).

Figure nine.v: Adapted from Sperling (1960).

Figure 9.6: Adapted from Peterson & Peterson (1959).

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontopsychology/chapter/8-1-memories-as-types-and-stages/

0 Response to "In Order to Remember His Lines for the Play He Repeates Over and Over Again"

Postar um comentário